Piece for Dazed and Confused on an excellent Dutch editor who makes books about vernacular pictures of Dalmatians and shooting galleries, thinks that there is something interesting in mistakes.

Erik Kessels is Creative Director at an amazingly interesting communications agency called KesselsKramer. Did you ever see that "I AMsterdam" campaign? That was them. As well as their advertising and design work, they make films, publish books and stage exhibitions. These books are always wonderful and often really funny and can be bought from their website, www.kesselskramerpublishing.com.

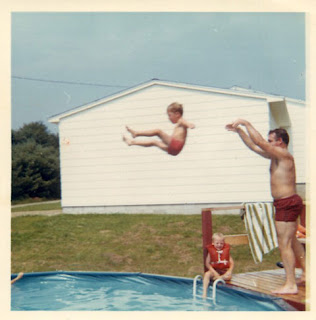

One of these – in almost every picture, a series celebrating found photos – caught our eye. Each book in the series is a collection of photographs sourced from flea markets, the internet and from found photo albums, "vernacular" pictures taken by "amateur" photographers. A family's library of pictures of its mischievous Dalmatian formed edition #5, a woman's record of 60 years of passport pictures formed #6, and #1 was a collection of remarkably consistent shots of a wife by her husband on holiday in Barcelona. They are getting quite famous and have been exhibited in Arles, Barcelona, New York and at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

Of course, like all vernacular photography, the joy of the shots is in the unsaid, anonymous nature of the photos and the stories you makeup to go along with them. But the genius of Erik and his team is the way that they draw the pictures together and the links between the pictures themselves: creating books that document, record and cross art, social history and personal biography. So, anyway, the books are in equal measure clever, tongue in cheek and tenderly humane and we emailed some questions over earlier. This is what he wrote back.

What is it that attracts you to vernacular photography?

Working in advertising means dealing with a lot of images that don’t appear to contain much of the real world. When I first discovered vernacular photography, I was struck by the freshness and naivety of its images, the amateurism of their composition, and the way in which the photographers make sometimes quite beautiful.

In a way, our work in both communications and books is a reaction against the hyperrealism of most commercial work. As a company, KesselsKramer aims to find something authentic in the things it makes. Even in the most commercial of posters, we always attempt to find a feeling of authenticity.

What makes an “in almost every” photo?

Mostly, it’s when the photo comprises part of a series that together form a certain story. These photographs were never intended to make a series, the people making them were entirely innocent of that goal. Nowadays, you see photo series appearing everywhere, particularly on blogs, but the difference is that blog series are created in order to be viewed as a whole. The books we publish contain images never intended to be arranged as a narrative and bound. This means they have a certain naïve, unforced quality.

How did you begin this quest?

I was once in a flea-market in Barcelona, surrounded by vases, secondhand mugs, all the usual paraphernalia you find in those places, but nothing you could call really personal. Then I saw 400 or so images on the ground, abandoned, a whole life story in pictures. It began to rain then so I saved them all.

How/where do you find the pictures?

All kinds of places: flea-market, the internet… I also have images sent to me by people who have heard of previous books.

What links the series?

There’s a high level of amateurism, of course, but it’s also about how each book demonstrates a unique pattern forming a unique story. There’s also an element of chance at the heart of each book’s creation. What I mean is: I never know when the next book will come along because it depends on when the next interesting item will surface.

Am I right in thinking that some series are by one photographer, some by several?

The book dealing with the Spanish woman and that dealing with the taxi driver are by the one photographer. The book about twins was shot by several photographers; professionals who specialized in taking pictures on promenades in the last century. In three of our issues there is no photographer at all, or at least, not a human one. The books about the deer, the photo-booth, and the woman shooting are all the result of some machine based mechanism. In the case of the deer, the photos were triggered automatically by motion sensor. The photo-booth series is of course the product of a machine activated shot, and the shooting gallery images were automatic too, prompted by a bullet exiting the rifle’s chamber.

Which is your favourite?

The first one, about the anonymous Spanish woman. I waited a few years before publishing it. A lot of people were saying that I had to do something with the images, and after the book came out I was contacted by a gallery in Barcelona who wanted to show them. People made a poster of the anonymous woman and asked her to come to the gallery, a stunt that was picked up and covered in many newspapers and other places. A couple of weeks later, an older woman visited the gallery and said she knew the woman. It turned out that they worked together in a telephone company, and for the first time we had a name: Josefina Iglesias. She’d died years ago, but still that completed the circle, suddenly she wasn’t so abstract but an actual concrete person.

With most of the books, I try to find a link, a way to trace the story back to its protagonists, to find the people we spend so much time looking at. That’s why the back of every book contains a message that if these photos belong to you, they will be returned.

Threads this month is on archiving. Do you regard yourself as an archivist?

To be honest, I’m not that interested in being an archivist. I’m more into telling stories about other people. Sometimes you need an archive for that so you can make links and make new stories, but an archive in itself is dead.

One of the themes of the series is the tension between amateurism and professionalism. Do you regard yourself as an amateur?

I wish I could regard myself as an amateur but I’m a professional. You can learn a lot from amateurs and the way they look at things. The have a clean slate, and they don’t have the same neurosis about mistakes found in professional work. Professionalism just says MAKE NO MISTAKES in big capitals, but maybe there is something interesting in mistakes because they’re the reason people often look at a piece- the error makes it jump out from a crowd of over-slick productions. With these publications, it’s more about showing regular people’s passion for images, and that means including and even celebrating the technical errors they make.

What does this series tell us about photography as a practice and as an art form?

In a way, it tells us that everyone is a photographer and that anybody can make a story.

Now, image-making is democratic, everyone can make photography, and with so many millions of people practicing the form, some very good talents will inevitably pop up.

Whether this is art or not doesn’t really matter to me personally, but for what it's worth the series of the woman shooting sparked an enormous debate recently centred on just this point. It was bought by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam a little while back, making it the first amateur series ever admitted to their collection. There’s a big discussion on the net right now about how the woman isn’t an artist so why should such a prestigious museum have taken her work.

Tell me about the future of the publishing house itself. How did you set it up, and what are your plans for the future, and how does KK Outlet fit in?

The books we publish are always produced by people in the office, never by outsiders, and it was with this intention that we set up our publishing arm. More overtly commercial work, like our Hans Brinker Budget Hotel book or our collected work, 2 kilo of KesselsKramer, would never be published by us because they aren’t personal fascinations. The plan is that as the publishing arm grows, maybe it will change, maybe involving others outside KK. KK Outlet is born out of the same thinking: to have as much diversity as possible within our output. We were producing enough work to fill a showroom, so we thought why not make a space to fulfil just such a purpose. The Outlet is the result, a combined gallery, shop and workspace.

Erik Kessels

www.kesselskramerpublishing.com

www.kkoutlet.com

No comments:

Post a Comment